Photographing LSD: An Interview with Lawrence Schiller

The Acid Test, Neal Cassidy. ©Polaris Communications Inc, Photo by Lawrence Schiller

I was 15 minutes early for my breakfast meeting with Lawrence Schiller. Already seated, the 79-year-old photojournalist was in the middle of responding to emails. A stack of tangible mail lay open on the table.

Schiller has made a career out of arriving early, including being one of the first reporters to discuss Lysergic Acid Dethylamide (LSD or LSD-25) on a mainstream level. While LSD is a household name these days, that wasn’t always the case.

“The first time I was introduced to acid was in Canter’s Delicatessen,” recalls Schiller. “I saw people staring at the tips of spoons. I didn’t know what it was all about. I asked somebody and they said, ‘they’re tripping on acid.’ Intrigued, Schiller began frequenting the popular late-night restaurant without his camera. “Canter’s became the hangout where everybody was tripping. It wasn’t long before I met people like [The Merry Pranksters] and Laura Huxley.”

Schiller’s interest in the hallucinogen was further stimulated when he heard about Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (Ram Dass), two psychologists who had researched psychedelics at Harvard. From what Schiller understood, when the University lost control over experiments being conducted by the two academics, Alpert was fired and Leary was not invited back. “Then I heard that they weren’t necessarily the best of friends anymore,” explains Schiller. “One was associating with wealthy people and the other [and I didn’t know which] was associating with more spiritual people.”

Schiller realized that a psychedelic revolution was underway and pitched the topic to LIFE magazine. Despite prior brief mentions in both LIFE and Time, Schiller claims LSD was still so uncommon that LIFE turned down the pitch, stating that the fad was nothing more than a local California story. “They weren’t interested at all. I knew the structure of the magazine and knew I wasn’t presenting enough credibility.”

Schiller says he then went to the medical editor at Time and pitched the idea of a shorter article, one that wouldn’t require photos. Time accepted the pitch and published an interview with Dr. Sidney Cohen, an LSD researcher whose views on acid were becoming progressively negative, and who had authored the book The beyond within: the LSD story. “The idea was that if Time ran the article, I could take it into LIFE and say, ‘Wow. Time is really interested in this, how could you not be?’ and that’s exactly what I did,“ says Schiller.

Other reports suggest that, unbeknownst to Schiller, Dr. Cohen had dosed Henry Luce, owner of both Time and LIFE, long before Schiller approached the media magnate. Schiller, on the other hand, opted never to try the drug. "You come up against two things: are you going to do a story from the inside or from the outside? I elected to do the story looking at the phenomenon from the outside. If you’re going to keep your objectivity from the outside, it would be improper to experiment with the drug. I made a conscious decision not to do that.”

Wanting approval from Leary, Schiller set up a casual lunch with the psychedelic pioneer at Hamburger Hamlet on Sunset Boulevard. “[Leary] was a prophet. Every fifteen or thirty words led to the fact that we need to make changes, that it’s better to make love than war,” describes Schiller. “Leary was against the indiscriminate use of acid, he said it had gotten out of hand.”

At the time, the former Harvard lecturer was facing felony charges in Texas for crossing the US / Mexico border with cannabis (found on his daughter Susan, but belonging to his future wife, Rosemary). Leary wanted Schiller to cover the trial, adding that it would be a good way to meet other LSD researchers. Alpert also attended the trial in support of Leary, marking the one time Schiller saw the former colleagues together. When asked to compare the two acid protagonists, Schiller describes Alpert as more of an introvert. “He said much less. You could feel things going over inside of him like a washing machine, turning over, turning over, turning over, and something would come out of it. Leary was more to the point, more exact.”

Schiller spent four to five months photographing people on acid, documenting a wide spectrum of emotions triggered by the drug. He created colorful time-lapse images to capture the vibrant energy at Ken Kesey’s Acid Tests (parties with light shows and music customized to simulate the LSD experience, and where the drug was given out for free). He shot in black and white when illustrating the intimacy and intensity of apartment sessions.

Schiller says no participants expressed regret, but is reminded of an incident that occurred while shooting a teenage girl in a grocery store, tripping out on the designs of cereal boxes. “She left the store and wound up in the street in an unhealthy situation.”Refusing Schiller’s persistence to take her to the hospital, she instead requested he take her home to Scarsdale, New York. Schiller purchased two plane tickets and chaperoned the teenager on a red-eye flight across the nation, arriving at her mother’s doorstep early the next morning.

Her mother broke down crying when she opened the door. Schiller says, “Her mother went crazy,” thinking he had been with her the whole year she had been missing. “She was 18. Her daughter had been a runaway.” The police were called and they questioned the LIFE representative, who was in his late thirties at the time, until the mother was convinced he had done nothing wrong.

LIFE Magazine, March 25, 1966

Published on March 25th, 1966, LIFE’s ten-page cover story was compiled by multiple writers. It provided facts, testimonials, and first-hand accounts by various users including a recollection from a Republican businessman.

In his 1983 autobiography Flashbacks – in which Schiller is mentioned in the acknowledgements for “visual support” – Leary credits the LIFE piece as the “most convincing endorsement of LSD and an eloquent plea for nonmedical research,” adding that it was obvious when the piece was published that it “would double the number of consumers.”

On the cover, LSD was introduced as an “exploding threat,” causing critics to interpret the piece as a scare tactic. It’s understandable that the essay’s coverage of bad trips would frighten those who had never heard of mind-expanding drugs, which was most of America. But overall, the essay reads as a detailed, unbiased profile of the drug’s emergence into society.

Shortly after the LIFE essay was published, Schiller received a phone call from someone at Capitol Records stating that Alan Livingston, the label’s president who had signed The Beatles, wanted to meet him. At Capitol’s historic circular-shaped headquarters near Hollywood and Vine, Livingston confided in Schiller that a loved one of his had been taking acid until Dr. Cohen showed him an alternate way. The record executive then proposed the idea of a documentary album exploring LSD, both the good and the bad, and asked Schiller to produce it.

The LSD Album Cover, 1996, photo by Lawrence Schiller

Narrated by American Bandstand’s Dick Clark, the album mixes music with interviews and audio of people on acid. Among those appearing are Leary, Dr. Cohen, Laura Huxley, and Allen Ginsberg. The album aired on FM radio and profits from vinyl sales were donated to the Los Angeles Medical Research Foundation to support studies on the drug.

On the album, Ginsberg shares helpful advice of how to manage trips: “If you see anything horrible, don’t cling to it. If you see anything beautiful, don’t cling to it.” Huxley compares the danger of the substance to that of falling in love. The more positive statements on the album are overshadowed by Clark’s description of teenagers chewing bark off trees and growling like dogs.

While the intention was to deliver a well-rounded documentation of LSD, the album poses the same conundrum as the LIFE article. Imagine a mother driving, listening to the radio. All of a sudden, Dick Clark comes on announcing a “nationwide crisis” involving a colorless, odorless liquid that is “as easy to obtain as a hamburger at a local drive-in.”

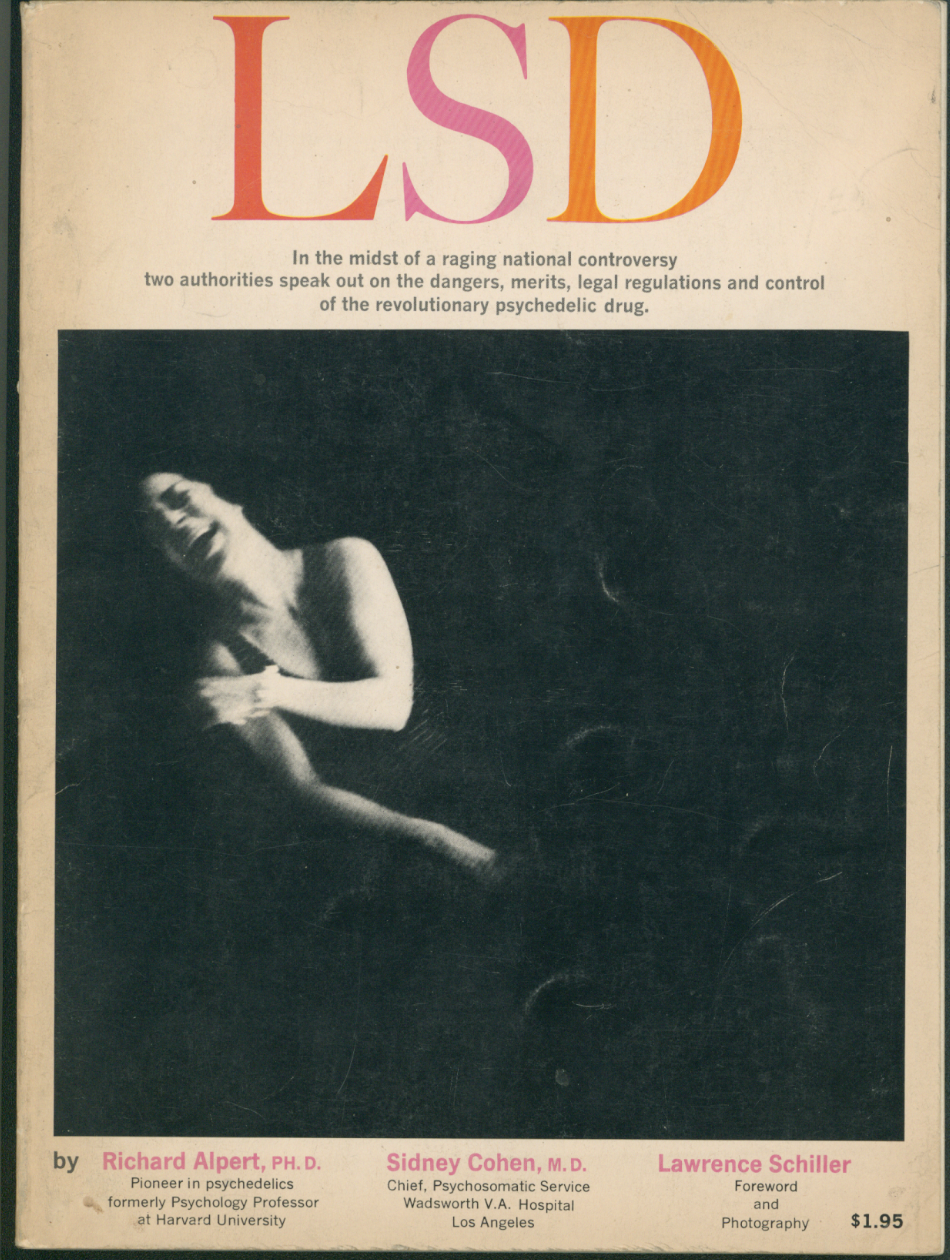

Knowing there were lingering questions regarding the use of acid, Schiller also made a book pressing for answers. Featuring Alpert and Cohen discussing their opposing views of acid, alongside photos of people tripping, the book, titled LSD, became a bestseller.

Cover of the bestselling book, LSD, 1966

Inspired by Schiller’s work, Tom Wolfe interviewed him when doing research for The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. The two are currently collaborating on a limited-edition TASCHEN book that will wed Schiller’s photographs illuminating the world of acid in the 1960s, with a 55,000-word excerpt from The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Despite differences in personal drug use, Schiller and Leary remained friends. Following a night when Leary dropped acid in the photographer’s living room, Schiller’s seven-year-old daughter said to her father, “That man [Leary] has his way of being happy and you and mommy have your way of being happy.”

With LSD’s recent reemergence into government-funded research, Schiller continues to support its use. “Society exists on the use of substances for various purposes. I had cardiac arrest in 2002. I was dead for a minute and thirty-seven seconds. I was brought back on the third jolt. I take five pills a day – three in the morning, two at night. Those pills, one might say, keep me alive. If one of those pills was LSD, then fine. It’s a matter of what is beneficial for society and how people live their lives.”

*This article was originally published in Riot of Perfume, Issue 7